D’Angelo and the Celebration of Afro-Caribbean Culture

Within the first few hours of news that D’Angelo had succumbed to pancreatic cancer, a couple of my friends contacted me. All the calls and the texts that came in its wake followed the same sentiment of: “Davey, you heard the news?”

Born Michael Archer in Richmond, Virginia, D’Angelo’s legacy is largely tied up with music that emerged in the mid to late 90’s that would be marketed as “neo soul”. His 1995 Grammy-nominated debut album, Brown Sugar - which he wrote, produced, composed and arranged as a teenager - was the catalyst for this unique sound of music that blend R&B, Jazz, Hip-Hop and Soul. Still in recent years, D’Angelo has pushed back against this categorization of his music. For as he told Red Bull Academy in a 2014 public lecture:

“I never claimed I do neo-soul, you know. I used to say, when I first came out, I used to always say, 'I do Black music. I make Black music”.

It is within this context that lies D’Angelo’s greatest legacy – the manner in which he used his music as a medium of the Black experience. For me, that is what D’Angelo’s music is – an experience that was unapologetically Black; and anyone who was up for it, will be subjected to my dissertation level analysis of this fact. He drew upon the works of pioneers before him to shape a future of what happens when art, in the hands of Black people, is given time and space to be dissected, studied, worshiped and reimagined without capitalistic and predatory influences. His music (spread across three studio albums, a live album and a compilation project) challenges the preconceived limitations of this Black expression. As such, D’Angelo’s discography was never confined to the borders of the United States, but drew upon the unique cultures that exist within the Black diaspora – the Caribbean included.

Most evidence of Black Caribbean culture in D’Angelo’s discography was his widely acclaimed sophomore album, Voodoo. The album which came 5 years after his debut, was recorded in the legendary Electric Lady Studios. Coming off years of dealing with writer’s block and being unsatisfied with the music industry, D’Angelo would assemble some of the most revered musicians at this time to collaborate with. The group styled themselves “The Soulquarians” and featured the likes of Questlove, J Dilla, Erykah Badu, Common, Roy Hargrove, Q-Tip, among others. Some of the most acclaimed albums of the decade came out of this collective.

Voodoo is named after the West African derived tradition which is widely known for its Haitian derivative – Voudou. Still, the album was released when anti-black racism and anti-immigrant sentiments plagued Haitian refugees and immigrants in U.S. society and this speaks to the radical politics of the album. Up to this point, the only U.S. based musical act to acknowledge anything related to Haitian culture in their music was The Fugees.

Yet, Voodoo which put on display the religious reverence of music, pushed back on the negative stereotype of Voodoo traditions, which are often demonized and othered in Western media. The album gave it space to be celebrated. Thus, the role of Afro-religious traditions in Haiti’s political history should also be considered through this lens for the album. As Ryan Dombal stated in his review of the album for the music outlet, Pitchfork, (the album was given the rare perfect score of 10):

“While probably using voodoo's exaggerated and misrepresented image within modern popular culture to add some mystique and danger, D'Angelo's also likely referencing the religion's African origins, and how it was coveted by uprooted slaves, feared by slave owners, and ignited the Haitian Revolution of 1791”

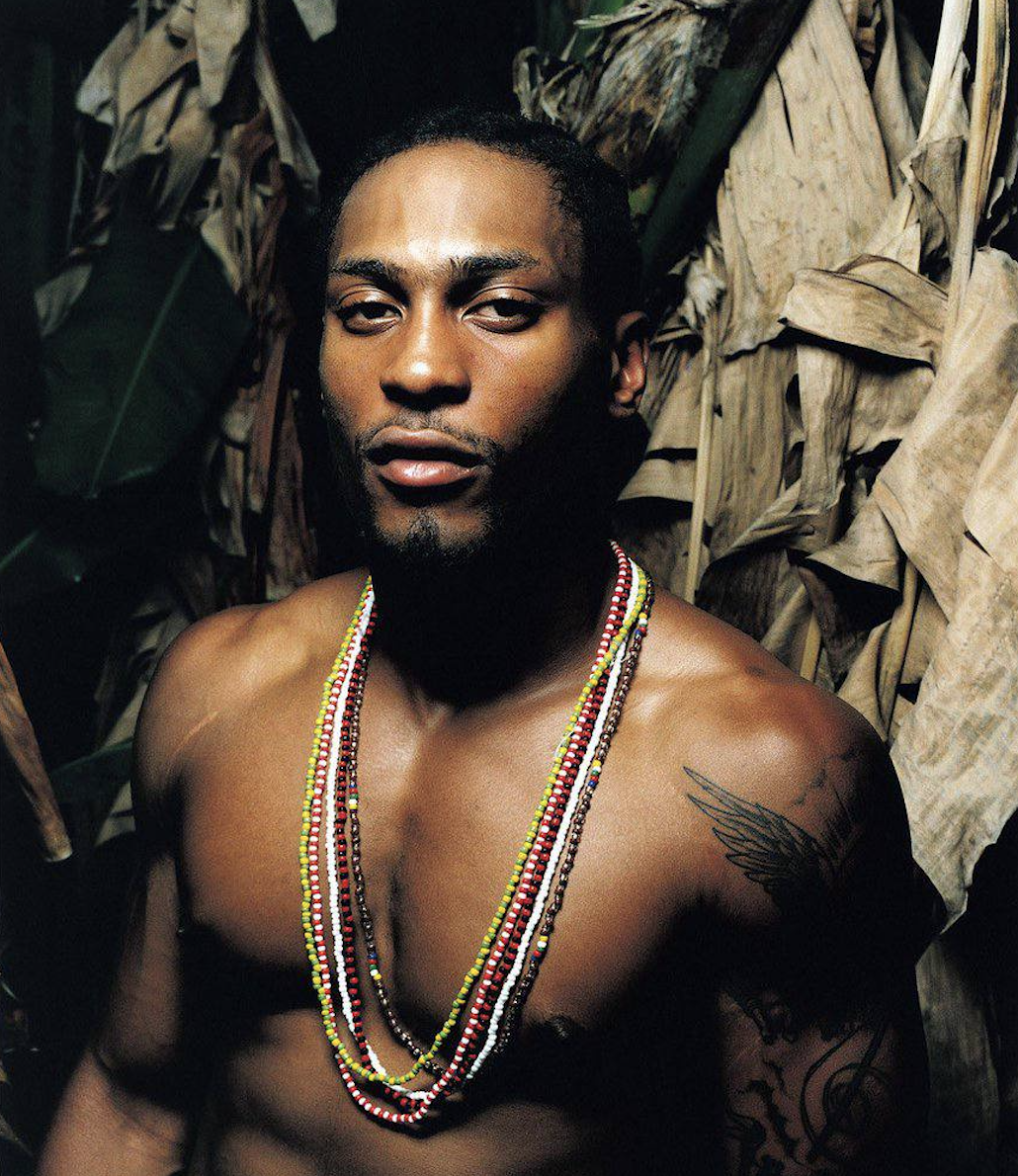

D'Angelo also tapped into Cuban religious culture for this album. Months before its release, D’Angelo and his team journeyed to Cuba to take promotional photos for the project. While there, he would take part in a Santería ceremony. Santería is the Afro-Cuban religion, which blends elements of Yoruba and Roman Catholicism. It is no wonder why it appealed to D’Angelo, the son of a Pentecostal pastor, who grew up leading the church choir. In pictures of the ceremony taken by Thierry Le Goues (who most people might know from his black and white pictures in Tommy’s House in Belly, the 1998 Hype Williams directed movie that was partially shot in Jamaica), D’Angelo is seen wearing ceremonial beads called elekes, which are insignia for the Orishas, deities in Santería. According to a February 2015 Facebook post by IFA: Òrìṣa Scientific Spirituality, the five elekes worn by D’Angelo represent Orisa Oya, Eshu, Shango, Obatala, and Orunmila.

D’Angelo wearing elekes while taking part in Santería ceremony in Cuba in 1999. Photograph: Thierry Le Goues

Other photos also show D’Angelo dancing with iyalochas (priestess in Santería) and playing the batá drums. In the Santería tradition, the batá drummers are called Omo Añá ("children of the spirit of the drum"), where the drums are used to communicate with the Orishas.

Then just like Haiti’s political history previously mentioned, one must view D’Angelo’s actions through the lens of Caribbean history. In 1816, the same year as the Bussa's Rebellion of Barbados, the Caribbean colonial overlords enacted a slave code that placed stricter regulations on Black enslaved people's gatherings and barred them from playing drums. According to the academic, Dr. Petal Samuel, who studies the anticolonial thought, politics and aesthetics in the Caribbean and its diaspora, this slave code was enacted because “the colonial authorities and planters were fearing that certain kinds of sounds could either signal or induce slave rebellions”.

As such, this history and D’Angelo playing alongside the Omo Añás gives context to his description of the album. As he told Jet Magazine in a 2000 interview:

“I named the album Voodoo because I really was trying to give a notion to how powerful music is and how we as artists, when we cross over, need to respect the power of music. Voodoo is ancient African tradition. We use ‘voodoo’ in the drums or whatever, the cadences and call-out to our ancestors and that in itself will invoke spirits. And music has the power to do that, to evoke emotions, evoke spirit. That’s something I learned in the church when I was very young and that’s what I wanted to get across.

D’Angelo taking part in Santería ceremony in Cuba in 1999. Photograph: Thierry Le Goues

In the end, these photos of D’Angelo appeared on the album’s vinyl release. Still, Santería went beyond the album’s graphic design– it eventually found itself on the album. The opening lines of the project, the first seconds of Playa Playa, is a scene from the aforementioned ceremony. In a 2020 interview with NPR, D’Angelo’s engineer, Russell Elevado, explained this when he was asked about “what’s going on” at the beginning of the album,

“That was actually a track that was recorded in Cuba. They went to take pictures for the album, and while they were there they were at a ceremony — like, Santería. So that's a remote recording of a real voodoo ritual”

Just as the drums are used to initiate both Santería and Voodoo ceremonies, so do they open D’Angelo’s album (ironically the album's final song is titled Africa). If anything, the album is a spiritual escape – a ceremony of some sort. As Dr. Loren Kajikawa would write in his paper, D'Angelo's Voodoo Technology: African Cultural Memory and the Ritual of Popular Music Consumption:

“D’Angelo’s Voodoo is an album in which nearly every song is built around sort of cyclic funk groove, and in the black religious cultures of the circum-Caribbean and United States alike, repetitive musical practices hold the key for participants to experience moments of spiritual transcendence.

Poet Saul Williams also expanded the parallels of Afro-religious traditions and contemporary music when he wrote in the linear lines of the albums:

“When you pour that wine on the ground in that video shoot that has become your life will you be ready to hear the voice that pours from the bottle to inebriate the very ground on which we walk? It is libations such as these that are the start of every voodoo ceremony”.

Furthermore, the reverence of Black women in these Afro-religious practices shines through D’Angelo’s music. On the album’s twelfth track, Untitled (How Does It Feel), the lines between lust, love and worship became blurred. On prior projects, he would address this veneration and awe of Black women. As he sang on his duet with Ms. Lauryn Hill, Nothing Even Matters:

“I sometimes have a tendency

To look at you religiously

Cause nothing even matters, to me”

Still, while this worship of Black women through his music might come as news to some, Danielle Amir Jackson makes the case that Black women, who are fans of D’Angelo, have always known this fact. As she wrote for The Guardian:

“Female listeners, especially, had long been attuned to his art. We could sense, perhaps, the women inside his sound. Even when he sang alone, his music carried the influence of female collaborators, muses, ministers, and church mothers who shaped his voice, his arrangements, and his emotional acuity.”

D’Angelo would also tap into Caribbean music in the making of Voodoo. In the 33 1/3 book series, Faith Pennick wrote about the album where she interviewed Charlie Hunter who recalled that D’Angelo instructed him and other musicians on the album “to play really behind the beat, so far behind the beat that it sounds uncomfortable”. This technique, Hunter explained, had its roots in Cuban music which he described as, “so incredibly advanced, creatively”.

Then, on the album’s ninth track, Spanish Joint, D’Angelo played keys as he collaborated with some of music’s most revered instrumentalists – Questlove (drums), Charlie Hunter (bass & guitar), Giovanni Hidalgo (congas) and Roy Hargrove (horn) - to create a record that merged Latin grooves with Afro-Cuban Jazz, R&B and Funk. In incorporating these genres on the song, D’Angelo showed his appreciation for the different Black expressions across the diaspora. As he stated:

“I'm making black music. That's the only outline for me, really. That's the only boundary to stay with. It's soul music. I'm going all out in those terms”

A year after its release, Voodoo received the Grammy for Best R&B album and D’Angelo gained another when Untitled (How Does It Feel) won the Grammy for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance. In 2024, it appeared 57th on Apple’s 100 Best Albums while it was ranked 11th on Rolling Stone’s Best Album of the 21st Century list.

Almost fourteen years after his acclaimed sophomore album, the famously reclusive singer would mark the formal end to his self-imposed exile from music. That summer, D’Angelo was one of the headline acts at Afro-Punk where during his set, he and The Roots perform an incredible funk rendition of The Wailer’s Burnin' And Lootin’. This cover would serve as a prelude of what was to come for almost three months later, D’Angelo, joined by his own band, The Vanguards, would release his third studio album Black Messiah. Released in the wake of numerous police brutality incidents against Black people in the U.S., the album, just like The Wailers’ Burnin', serves as a call for political action against injustice

Black Messiah, which would appear on numerous “best albums of the year” lists and earned a Grammy for Best R&B Album, also explored themes of love, anxiety and spirituality. With this, it allowed for the listener, especially Black men throughout the diaspora, to confront the anxieties around their identity as they move through the world. For as Ms. Lauryn Hill said in her tribute to him in the wake of his death:

“You imaged a unity of strength and sensitivity in Black manhood to a generation that only saw itself as having to be one or the other.”

Then, the controversy around his decade long hiatus from the music scene, showcased the complexity around Black men’s relationship with being seen as humans beyond their sexual and physical desirability. This D’Angelo himself, would address on Back to the Future (Part I), track six off Black Messiah:

“So if you're wondering about the proper shape I'm in

I hope it ain't my abdomen that you're referring to"

As such, although Black Messiah does not have overtly Caribbean elements like that of Voodoo, its impact was still felt among Black West Indians. In a December 2024 interview with the Jamaica Gleaner as a part of their 5 Questions With... series, the acclaimed Jamaican producer J.L.L. said this when asked about the music currently on his playlist:

“Lemme tell you, that D’Angelo album, Black Messiah is a project [that] I [always] go back to. It’s a project that just makes me go inside myself. It makes me really just feel like a black man. When I listen to that it’s like the top of where I wanna be in music, that album, Black Messiah. I don’t listen to it as often ‘cause I don’t want to play it out, but when I do, it never ceases to amaze me.”

Since Tuesday, there has been an outpouring of tributes to the musical genius whose legacy gave everyone permission to give themselves time and grace to study, appreciate and explore their different creative interests. It is with this, that I hope that he is finally at peace and somewhere, in another life, having a jam session with his friends, Roy Hargrove and J Dilla - both whose lives were also cut short due to illness. It is also this hopefulness that drives my response when my friends inquire on my mood when news dropped of the death of one of my favourite musicians – “Life is hard but we’ll be fine”

An abridged version of this article was first published in the Jamaica Gleaner under the heading, When the Music Became Ceremony: D’Angelo’s Caribbean Connection